Please allow 10 working days to process before shipping

10oz Alpine Green Hoodie

80% cotton 20% polyester

“The purpose of a system is what it does.” - Stafford Beer

Stafford Beer

Beer was an eclectic 20th century British theorist who achieved remarkable innovations in the seemingly disparate fields of capitalist management consulting and state-sponsored socialism. He believed that cybernetics (what he called “the science of effective organization”) represented a new frontier in institutional and organizational design, a powerful tool that would inevitably be taken up if not by the forces of democracy and freedom then by their enemies, authoritarians of either the corporate or government variety (if not both).

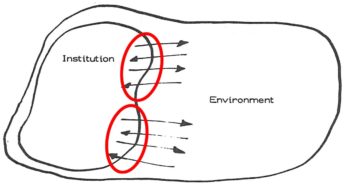

Brian Eno described him lovingly, “he was all hair and brains: full of life, fuller of opinions, intimidatingly fast and yet encouraging. He spoke to me not as a student but as a peer. This was demanding: his mind moved quickly.” One of Eno’s favorite quotes would be a fundamental guiding principle for his work: “instead of trying to specify in full detail,” Beer wrote in his book The Brain of the Firm, “you specify it only somewhat. You then ride on the dynamics of the system in the direction you want to go.” As he asks in Designing Freedom, “What should be done with cybernetics? … Should we all stand by complaining and wait for someone malevolent to take it over and enslave us? An electronic mafia lurks around that corner.” Beer explains this "surveillance capitalism" in a one page drawing, from "The Risk of an Electronic Mafia" (1973).

Stafford Beer (25 September 1926 – 23 August 2002) was a British theorist, consultant and professor. He is best known for his work in the fields of operational research and management cybernetics, as well as the architect of Cybersyn, a Chilean project from 1971-73 during the presidency of Salvador Allende which aimed at constructing a distributed decision support system to aid in the management of the national economy.

As Eden Medina shows in “Cybernetic Revolutionaries,” her entertaining history of Project Cybersyn, Beer set out to solve an acute dilemma that Allende faced. How was he to nationalize hundreds of companies, reorient their production toward social needs, and replace the price system with central planning, all while fostering the worker participation that he had promised? Beer realized that the planning problems of business managers—how much inventory to hold, what production targets to adopt, how to redeploy idle equipment—were similar to those of central planners. Computers that merely enabled factory automation were of little use; what Beer called the “cussedness of things” required human involvement. It’s here that computers could help—flagging problems in need of immediate attention, say, or helping to simulate the long-term consequences of each decision. By analyzing troves of enterprise data, computers could warn managers of any “incipient instability.” In short, management cybernetics would allow for the reëngineering of socialism—the command-line economy.

Cybersyn never really took off. Stafford had hoped to install “algedonic meters” or early warning public opinion meters in “a representative sample of Chilean homes that would allow Chilean citizens to transmit their pleasure or displeasure with televised political speeches to the government or television studio in real time.” Stafford dubbed this undertaking ‘The People’s Project’ and ‘Project Cyberfolk’ because he believed the meters would enable the government to respond rapidly to public demands, rather than repress opposing views.

Ultimately, according to Stafford, Cybersyn did not succeed because it wasn’t accepted as a network of people as well as machines, a revolution in behavior as well as in instrumental capability. In 1973, Allende was overthrown by the military and the Cybersyn project all but vanished from Chilean memory.

A self-organized system must be always alive and without finalizing, since conclusion is another name for death.

Stafford Beer was deeply shaken by the 1973 coup, and dedicated his immediate post-Cybersyn life to helping his exiled Chilean colleagues. He separated from his wife, sold the fancy house in Surrey, and retired to a secluded cottage in rural Wales, with no running water and, for a long time, no phone line. He let his once carefully trimmed beard grow to Tolstoyan proportions. A Chilean scientist later claimed that Beer came to Chile a businessman and left a hippie. He gained a passionate following in some surprising circles. In November, 1975, Brian Eno struck up a correspondence with him. Eno got Beer’s books into the hands of his fellow-musicians David Byrne and David Bowie; Bowie put Beer’s “Brain of the Firm” on a list of his favorite books.

Isolated in his cottage, Beer did yoga, painted, wrote poetry, and, occasionally, consulted for clients like Warburtons, a popular British bakery. Management cybernetics flourished nonetheless: Malik, a respected consulting firm in Switzerland, has been applying Beer’s ideas for decades. In his later years, Beer tried to re-create Cybersyn in other countries—Uruguay, Venezuela, Canada—but was invariably foiled by local bureaucrats.

Cybernetics is one of the most widely misunderstood concepts. Cybernetic systems have been used to model all kinds of phenomena, with varying degrees of success - factories, societies, machines, ecosystems, brains—and many noted artists and musicians derived inspiration from this powerful conceptual toolkit. Cybernetics may be one of the most interdisciplinary frameworks ever devised; its theories link engineering, math, physics, biology, psychology, and an array of other fields, and ideas from cybernetics inevitably infiltrated the arts. The musician and producer Brian Eno, for example, was a big fan of connecting ideas from cybernetics to the studio environment, and to music composition, in his work in the 1970s.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/10/13/planning-machine

Technics— an excerpt from The Ecology of Freedom by Murray Bookchin

Bookchin wrote of his word choice in the title: Put quite simply, ecology deals with the dynamic balance of nature, with the interdependence of living and non living things. To the modern mind, technics is simply the ensemble of raw materials, tools, machines, and related devices that are needed to produce a usable object. The ultimate judgment of a technique's value and desirability is operational: it is based on efficiency, skill, and cost. Indeed, cost largely summarizes virtually all the factors that prove out the validity of a technical achievement.

But to the classical mind, by contrast, "technique" (or techné) had a far more ample meaning. It existed in a social and ethical context in which, to invoke Aristotle's terms, one asked not only "how" a usevalue was produced but also "why." From process to product, techné provided both the framework and the ethical light by which to form a metaphysical judgment about the "why" as well as the "how" of technical activity.

"All art [techné] is concerned with coming into being, that is, with contriving and considering how something may come into being which is capable of either being or not being, and whose origin is in the maker and not in the thing made." Accordingly, techné is a "state concerned with making, involving a true course of reasoning. . . ." It is "potency," an essential that techné shares with the ethical "good." All "arts, i.e., productive forms of knowledge, are potencies; they are originative sources of change in another thing or in the artist himself considered as other.” An authentic community is not merely a structural constellation of human beings but rather a practice of communising.

Designing Freedom

Beer explicitly rejects the centralization vs. decentralization framing—in Designing Freedom he notes that he has “seen the two policies advocated alternatively for the same institution by successive groups of consultants.” Instead, what matters to Beer is the relationships between different layers of a system: whether the actors at each level have appropriate, timely information from below and above, and the extent to which they are empowered to act. In other words, both capitalist and state socialist organizations can fail by reducing their human agents to mere machines, preventing the flow of information necessary to adapt to a complex and continually changing world. Rather than deduce a system’s politics by the predilections of its designers or its degree of centralization, it is more important to appreciate how it adjusts itself.

Much of his work from the 1960s and 1970s, including his monumental The Brain of the Firm, has been influential in academic research and business school curricula, particularly his “viable system model,” which was innovative in its orientation toward improving information and feedback flows within a company.

The same year as the Allende coup, Beer gave a series of lectures for CBC Radio that would become Designing Freedom. There he outlines an argument for how new information technology—at the time, just fax machines and a handful of computers less powerful than a contemporary laptop — enables humans, as the apparently oxymoronic title suggests, to “design freedom.” In Beer’s view, the capacity of computers to communicate instantaneously across distances and to perform inhuman feats of computation allows for institutions that would permit humans to use their full capacities, collectively and at scale.

Based on the Massey Lectures, Designing Freedom examines the reasons why the institutions of our society may well be failing, and opens a discussion as to what could be done. Drawing on the science of effective organization, which is his definition of cybernetics, Stafford Beer explains key cybernetic principles in words and pictures that all can understand. He concludes that our society commits more and more resources to plastering over the cracks in the system which simply reappear while freedom itself is increasingly eroded. The institutions must be redesigned, and returned to the people, to whom the scientific tools for doing this ought to belong.

Beer’s Designing Freedom offers an interesting but wayward introduction to cybernetic (systems) thinking. In some respects the book looks quite dated. Contemporary readers may wonder why Beer makes such a fuzz of computers, still a relatively rare phenomenon in 1974 but more than ubiquitous in our world today. Also the author’s rather hectoring, messianic tone doesn’t fit the superficially genteel mood of our times. However, the book is still highly topical for readers today as it introduces a number of valuable ideas that help to shed light on our contemporary predicament.

Designing Freedom is basically a bundle of lectures, which means it is nice and short, and also you can listen to it on audio from Mr. Beer himself. The audio versions are actually quite nice to listen to, especially if you find people making very dry jokes in a British accent soothing, which I do. Beer’s texts are accompanied by simple drawings that illustrate his ideas nicely.

https://reallifemag.com/tipping-the-scale/

The Advanced Cat-Thread Theory of System Design

Two people each sit atop a pole which is stabilized by wires that run from the top of the pole down to the ground. Each person holds the end of a length of thread. From the center of that thread hangs another thread with a tennis ball at the end. Nearby, there’s a cat just hanging out, watching all this transpire.

The job of these two people is to keep that tennis ball steady. They each do their best to balance on their poles, which are also slightly unsteady. Each person’s small corrective movements and adjustments help stabilize the tennis ball, but when they’re not in sync, the efforts to stabilize can actually introduce inadvertent instability. All they can do is continually re-adjust to counter all this.

But there’s that dang cat down there, and it just can’t resist batting the ball around. The cat is arbitrary interference. The tennis ball’s stability is completely smacked away, and the two people in charge of keeping the ball steady have to do whatever they can to bring it back to a more stable state.