“La Révolution Surréaliste” began publication almost immediately after the appearance of André Breton’s (1896-1966) First Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. The magazine came out with no great regularity, twelve issues appearing between the first issue and the last, dated December 1929. Like the movement of which it was the voice, the politics of “La Révolution Surréaliste were of the left,” but with a unique flavor.

The magazine contained accounts of dreams, automatic writing, attacks on university leaders and the pope, roundtable discussions on suicide and sex, praise of the Marquis de Sade by the future Communist Paul Eluard, the scenario of the Surrealist film “Un Chien Andalou" by Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel, and art work by those close to or admired by the movement.

André Breton marked his definitive break with Dada with the release of his Manifeste du surrealisme; Poisson soluble in 1924. This treatise established Breton's position as the leader of Surrealism and earned him the support of many who had previously participated in the Paris Dada group. In his Manifeste du surrealisme, Breton officially renounced Dada and gave a formal definition for Surrealism:

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.

The manifesto explained the role artists could play in exposing the real nature of these systems. It rejected controls on artistic expression: "In the realm of artistic creation, the imagination must escape from all constraint and must under no pretext allow itself to be placed under bonds… and we repeat our deliberate intentions of standing by the formula, complete freedom for art".

La Révolution Surréaliste set out to explore a range of subversive issues related to the darker sides of man's psyche with features focused on suicide, death, and violence. Modeled after the static format of the conservative scientific review La Nature, the sober and uninspired format was deceiving, and much to the delight of the Surrealist group, La Révolution surréaliste was consistently and incessantly scandalous and revolutionary.

"The surrealist approach stands against the established order, against bourgeois values and proposes an ethics centered on freedom, desire, passions."

Like Dada, the Surrealist program was marked by pessimism, defiance, and a desire for revolution. Under Breton's leadership, however, Surrealism sought productive, rather than anarchic, responses to the group's convictions. Much like Dada, the history of the Surrealist movement can be traced through its many journals and reviews. December 1, 1924, was the inaugural issue of La Révolution surréaliste, the cover announces the revolutionary agenda of the journal: "It is necessary to start working on a new declaration of human rights.” Made up of many different individuals and trends, incorporating many different ideas, using a variety of media, surrealism was an overwhelmingly radical, left-wing movement.

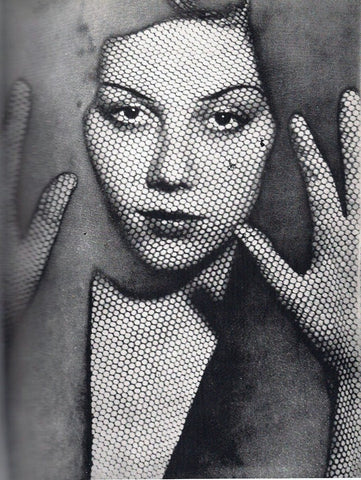

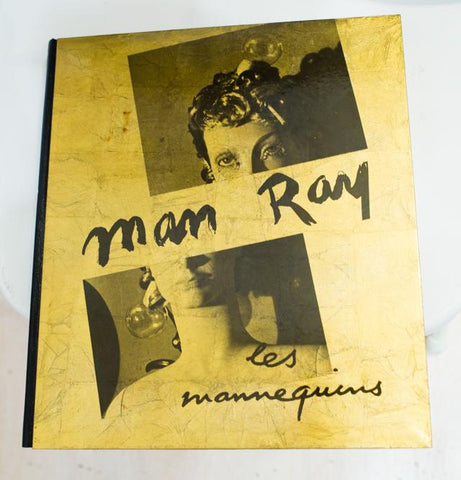

Photography came to occupy a central role in Surrealist activity. In the works of Man Ray and Maurice Tabard, the use of such procedures as double exposure, combination printing, montage, and solarization dramatically evoked the union of dream and reality. Other photographers used techniques such as rotation or distortion to render their images uncanny.

This impulse to uncover latent Surrealist affinities in popular imagery accounts, in part, for the enthusiasm with which Surrealists embraced Eugene Atget’s photographs of Paris. Published in La Révolution Surréaliste in 1926 at the suggestion of Berenice Abbott and his neighbor, Man Ray, Atget’s images of vanished Paris were understood not as the work of a competent professional or a self-conscious artist but as the spontaneous visions of an urban primitive—the Henri Rousseau of the camera. In Atget’s photographs of the deserted streets of old Paris and of shop windows haunted by elegant mannequins, the Surrealists recognized their own vision of the city as a “dream capital,” an urban labyrinth of memory and desire.

In Atget, Berenice Abott recognized a photographic master and a mentor, referring to his poetic Parisian street scenes and studies as “realism unadorned.”

After Atget’s death, in 1927, Berenice Abbottrescued his 5,000 prints and 1,000 negatives, eventually finding a home for the archive, with the help of Julian Levy, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In Atget she recognized a photographic master and a mentor, referring to his poetic Parisian street scenes and studies as “realism unadorned.”

But the Surrealist understanding of photography turned on more than the medium’s facility in fabricating uncanny images. Just as important was another discovery: even the most prosaic photograph, filtered through the prism of Surrealist sensibility, might easily be dislodged from its usual context and irreverently assigned a new role. Anthropological photographs, ordinary snapshots, movie stills, medical and police photographs—all of these appeared in Surrealist journals like La Révolution Surréaliste and Minotaure, radically divorced from their original purposes.

Whereas the ‘official’ history of surrealism tends to focus on its male leaders, a number of women played significant roles in its artistic and political life. By the end of the 1920s, for example, Denise Naville (née Lévy) and her husband, Pierre, both pioneers of surrealism, devoted themselves to the anti-Stalinist cause. Denise Naville, a key link between the French surrealists and German artists, translated Trotsky’s writings into German, along with works by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and others. (Surrealist Women, edited by Penelope Rosemont)

Surrealism was also strongly influenced by new, groundbreaking psychological theories, in particular Freudian psychoanalysis, and Breton's definition of "pure psychic automatism" So, just as society had to be freed from the restrictions of ruling-class control, thought could also be liberated.

"This is a true declaration of war that the surrealists are launching into society and they will remain, until the end, animated by a visceral hatred against bourgeois morality."

The title of issue 8 was derived from a quotation from Engels, one of the founding philosophers of communism, ‘Ce qui manque à tous ces messieurs c’est la dialectique’ (’What we lack is dialectic’), reproduced in capitals on the cover of La Révolution surréaliste (1926). Man Ray later clarifies, ‘Actually, I had in mind “imagination”, not dialectics, what we all lack is imagination’

In the twelfth and final issue of La Révolution Surréaliste (December 15, 1929), Breton published the "Second Surrealist Manifesto." This declaration marks the end of the most cohesive and focused years of Surrealism and signals the beginning of disagreement among its many members. Breton celebrated his faithful supporters and spitefully denounced those members who had defected from his circle and betrayed his doctrine.