Please allow 10 working days to process before shipping

8 piece wood block set

Hand painted & printed

Total cube size 4.5"

Guest Boot #14 - Are.na is a visual organization tool designed to help you think and create. It lets you build simple collections of content by adding links and files of any kind. Connect ideas with other people by collaborating privately or building public collections for everyone.

Feynman’s Tips on Physics - Triangulation

It will not do to memorize the formulas, and to say to yourself, “I know all the formulas; all I gotta do is figure out how to put ’em in the problem!” Now, you may succeed with this for a while, and the more you work on memorizing the formulas, the longer you’ll go on with this method—but it doesn’t work in the end. You might say, “I’m not gonna believe him, because I’ve always been successful: that’s the way I’ve always done it; I’m always gonna do it that way.” You are not always going to do it that way: you’re going to flunk— not this year, not next year, but eventually, when you get your job, or something—you’re going to lose along the line somewhere, because physics is an enormously extended thing: there are millions of formulas! It’s impossible to remember all the formulas—it’s impossible! And the great thing that you’re ignoring, the powerful machine that you’re not using, is this: suppose Figure 1-19 is a map of all the physics formulas, all the relations in physics. (It should have more than two dimensions, but let’s suppose it’s like that.)

Now, suppose that something happened to your mind, that somehow all the material in some region was erased, and there was a little spot of missing goo in there. The relations of nature are so nice that it is possible, by logic, to “triangulate” from what is known to what’s in the hole.

And you can re-create the things that you’ve forgotten perpetually—if you don’t forget too much, and if you know enough. In other words, there comes a time—which you haven’t quite got to, yet—where you’ll know so many things that as you forget them, you can reconstruct them from the pieces that you can still remember. It is therefore of first-rate importance that you know how to “triangulate”—that is, to know how to figure something out from what you already know. It is absolutely necessary. You might say, “Ah, I don’t care; I’m a good memorizer! I know how to really memorize! In fact, I took a course in memory!” That still doesn’t work! Because the real utility of physicists—both to discover new laws of nature, and to develop new things in industry, and so on—is not to talk about what’s already known, but to do something new— and so they triangulate out from the known things: they make a “triangulation” that no one has ever made before.

In order to learn how to do that, you’ve got to forget the memorizing of formulas, and to try to learn to understand the interrelationships of nature. That’s very much more difficult at the beginning, but it’s the only successful way.

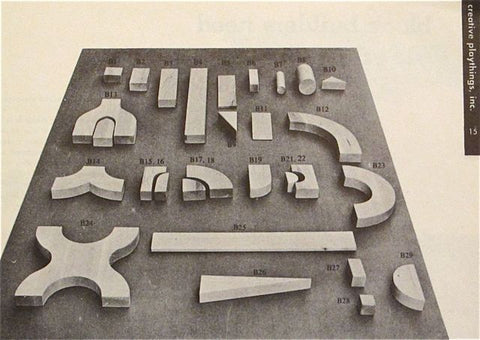

Macedonia coop blocks

ACCURATE IN FEELING IF NOT IN DETAIL

ACCURATE IN FEELING IF NOT IN DETAIL

In 1947, Macedonia, a small cooperative community in rural Georgia was looking for a way to keep their cooperative financially afloat. False starts involving broilers and persimmon pies left the young entrepreneurs ready to listen when visiting educators urged them to supply the nursery school movement with play equipment made from their 600 acres of woodland. A teacher from Caroline Pratt’s City and Country School in Manhattan introduced Pratt’s modular Unit Block design, based on the 1⅜" x 2¾" x 5½" unit, opened up a completely new vocation for them. The community then had a product and a powerful connection to the field of early childhood education: the concept of open-ended play.

The unit block principle was popularized by educator Caroline Pratt in the early 1900s. Pratt based her blocks on a similar but larger-scale block system designed by educator Patty Hill, a follower of Friedrich Fröbel, the originator of kindergarten education. Caroline Pratt was trying to figure out a good way to bring the world into the classroom. She wanted to help children discover the world by re-building it in miniature. The “unit blocks'' were her solution.

Pratt couldn’t patent her Unit Blocks—in them she had discovered something too basic to claim, as if she had invented water—but their acceptance by day care centers and nursery and elementary schools is by now close to unanimous.

The blocks, which were designed to mimic architecture, ended up influencing architecture itself. Kindergarten’s emphasis on geometry and abstraction has a part to play in the beginning of abstract art and modern architecture—Frank Lloyd Wright, for example, was one of the first generation of students in Froebel-style kindergarten, and fondly remembered his unit blocks.

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1222

Amy F. Ogata, “Creative Playthings: Educational Toys and Postwar American Culture.” Winterthur Portfolio, 2004

Patrick Geddes’ Outlook Tower

Scottish geographer, biologist, sociologist and town planner Patrick Geddes bought a tower next to the Edinburgh Castle in 1892. In over 20 years, he transformed it into an inhabitable device to illustrate his thoughts on visual faculties and the relationship between the individual and the exterior reality.

Renamed “The Outlook Tower,” the building became a permanent exhibition space. It is conceived on a vertical sequence of spatial experiences of contrasting nature which the visitor would go through; from steep helicoidal stairs, to a roof-top terrace, a darkened room and the Meditation Cell, a confined, windowless room.

The tower already featured a camera obscura at the moment Geddes purchased it. The natural phenomenon was enhanced by a mirror which would reflect the light through a system of lenses, into a darkened space where the projection of the exterior landscape was visible on a circular white table.

The section of the tower reflects Geddes’ idea that to reach an understanding of the whole universe one should start from a local point of view and progressively increase the scope of the vision without forgetting the different stages previously crossed. In this sense, a series of superposed rooms of the same size would contain information about “Edinburgh,” then “Scotland,” “English speaking countries,” “Europe,” and finally the “World.”

The visiting sequence started from the higher level of the tower with the observation of the actual outside reality of the Edimbourg landscape, from the terrace, it would then continue with the projected reality visible in real-time through the Camera Obscura. This progression considers the eye as the beginning of any journey toward the understanding of the world and its phenomena. Direct experience is the centre of knowledge in Geddes’ theory as in its physical manifestation through the Tower.

The Leith Observer quoted Geddes, to report that the main scope of the tower was to “graphically visualise an encyclopaedia of ordered knowledge and to outline a correspondingly detailed synergy of orderly actions. Regional survey thus passes into regional activity, and consequent regional development”

https://socks-studio.com/2020/12/27/from-vision-to-knowledge-patrick-geddes-outlook-tower-1892/

Memory Palace

Frances Yates’s The Art of Memory begins, like all classical treatises on the art, with the same story. One night the poet Simonides was invited to dine at the house of the famous boxer Scopas. Halfway through dinner, Simonides was summoned outside and, as he stepped through the door, the hall collapsed behind him. So complete was the wreckage that no one could identify the bodies of those who had died inside. No one, that is, except for Simonides, who, having committed the place of every guest at the table to his memory, was able to reunite grieving relatives with the remains of their loved ones.

Simonides, Yates tells us, was credited by all subsequent classical writers on the subject with the invention of the art of memory, which has at its heart a very simple principle. Simonides had been able to remember the names of the dead guests because he remembered where they had been sitting. The poets and orators of antiquity, who had to remember long passages of speech, believed that they could remember them better by assigning reminders—imagines—of small parts of them to imaginary places—loci. When the time came to recite the poem, or to make the speech, the speaker would take an imaginary stroll from locus to locus, being reminded of what to say in both in easily digestible chunks, and in the correct order.

In the late Roman Republic the orators Cicero and Quintilian were among those who developed the technique in their treatises on rhetoric – the art of public speaking from memory – and the way they wrote about it suggests that the art of memory was in common usage in the classical period. They called their constellations of imagines and loci “memory palaces,” and recommended that orators base them on real palaces and places that they had visited. The design of such palaces was precisely prescribed. Colonnades, for example, were not to be recommended in memory palaces because the loci between the columns were too repetitive to stimulate specific memories. Locations should be peaceful, and should respond to the scale of the human body.

The memory palace was imaginary, of course, and once the speech or the story it had been designed to recall was over, it was emptied of its contents. The orators of antiquity would then ready their memory palaces for new occupants: devising new rooms, and colonnades as a new narrative structure required, seeking out new imagines to stimulate new memories. And in this way the old memory palace would have changed into a new one, ready to stimulate the mind to tell a new story. Like a folk tale, handed down by oral tradition, like a historic building, preserved and altered by each iteration of transmission, the memory palace evolved in the mind of the orator in response to evolving circumstances.

If every interior is a temporarily assembled memory palace, and every memory palace a storytelling device, then every interior tells a story. Walter Benjamin wrote: “To inhabit means to leave traces”

If every interior is a temporarily assembled memory palace, and every memory palace a storytelling device, then every interior tells a story. Walter Benjamin wrote: “To inhabit means to leave traces”

New Babylon

New Babylon is an anti-capitalist city perceived and designed in 1959-74 as a future potentiality by visual artist Constant Nieuwenhuys. Initially known as Dériville (from "ville dérivée", literally, "drift city"), it was later renamed New Babylon. Henri Lefebvre explained: "a New Babylon—a provocative name, since in the Protestant tradition Babylon is a figure of evil. New Babylon was to be the figure of good that took the name of the cursed city and transformed itself into the city of the future."

The goal was the creating of alternative life experiences, called "situations," Sarah Williams Goldhagen explained:

“In the 1950s, Constant had already been working for years on his "New Babylon" series of paintings, sketches, texts, and architectural models describing the shape of a post-revolutionary society. Constant's New Babylon was to be a series of linked transformable structures, some of which were themselves the size of a small city—what architects call a megastructure. Perched above ground, Constant's megastructures would literally leave the bourgeois metropolis below and would be populated by homo ludens—man at play. (Homo Ludens is the title of a book by the great Dutch historian Johan Huizinga.) In the New Babylon, the bourgeois shackles of work, family life, and civic responsibility would be discarded. The post-revolutionary individual would wander from one leisure environment to another in search of new sensations. Beholden to no one, he would sleep, eat, recreate, and procreate where and when he wanted. Self-fulfillment and self-satisfaction were Constant's social goals. Deductive reasoning, goal-oriented production, the construction and betterment of a political community—all these were eschewed.”

Nieuwenhuys' New Babylon was based on the idea that architecture itself would allow and instigate a transformation of daily reality. As Nieuwenhuys wrote:

“It is obvious that a person free to use his time for the whole of his life, free to go where he wants, when he wants, cannot make the greatest use of his freedom in a world ruled by the clock and the imperative of a fixed abode. As a way of life, Homo Ludens will demand, firstly, that he responds to his need for playing, for adventure, for mobility, as well as all the conditions that facilitate the free creation of his own life. Until then, the principal activity of man had been the exploration of his natural surroundings. Homo Ludens himself will seek to transform, to recreate, those surroundings, that world, according to his new needs. The exploration and creation of the environment will then happen to coincide because, in creating his domain to explore, Homo Ludens will apply himself to exploring his own creation. Thus we will be present at an uninterrupted process of creation and re-creation, sustained by a generalized creativity that is manifested in all domains of activity.”

A Pattern Language

A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction is a 1977 book on architecture, urban design, and community livability. A Pattern Language is structured as a network, where each pattern may have a statement referenced to another pattern by placing that pattern's number in brackets, for example: (12) means go to the Community of 7,000 pattern. In this way, it is structured as a hypertext.

It includes 253 patterns, such as Community of 7000 (Pattern 12) given a treatment over several pages; page 71 states: "Individuals have no effective voice in any community of more than 5,000–10,000 persons." It is written as a set of problems and documented solutions.

According to Alexander & team, the work originated from an observation.

At the core is the idea people should design their homes, streets, and communities. This idea comes from the observation that most of the wonderful places of the world were not made by architects, but by the people. — Christopher Alexander et al., A Pattern Language

The book uses words to describe patterns, supported by drawings, photographs, and charts. It describes exact methods for constructing practical, safe, and attractive designs at every scale, from entire regions, through cities, neighborhoods, gardens, buildings, rooms, built-in furniture, and fixtures down to the level of doorknobs. The patterns are regarded by the authors not as infallible, but as hypotheses.

Each pattern represents our current best guess as to what arrangement of the physical environment will work to solve the problem presented. The empirical questions center on the problem—does it occur and is it felt in the way we describe it?—and the solution—does the arrangement we propose solve the problem? And the asterisks represent our degree of faith in these hypotheses. But of course, no matter what the asterisks say, the patterns are still hypotheses, all 253 of them—and are, therefore, all tentative, all free to evolve under the impact of new experience and observation.” — Christopher Alexander et al., A Pattern Language, p. xv

“Some patterns focus on materials, noting some ancient systems, such as concrete, during adaption by modern technology, may become one of the best future materials:

We believe ultra-lightweight concrete is one of the most-fundamental bulk materials of the future.” — Christopher Alexander et al., A Pattern Language, p. 958

“Other patterns focus on life experiences such as the Street Cafe (Pattern 88):

The street cafe provides a unique setting, special to cities: a place people can sit lazily, legitimately, be on view, and watch the world go by. Encourage local cafes to spring up in each neighborhood. Make them intimate places, with several rooms, open to a busy path, so people can sit with coffee or a drink, and watch the world go by. Build the front of the cafe so a set of tables stretch out of the cafe, right into the street. — Christopher Alexander et al., A Pattern Language, p. 437,439

Grouping these patterns, the authors say, they form a kind of language, each pattern forming a word or thought of a true language rather than a prescriptive way to design or solve a problem. As the authors write on p xiii, "Each solution is stated in such a way, it gives the essential field of relationships needed to solve the problem, but in a very general and abstract way—so you can solve the problem, in your way, by adapting it to your preferences, and the local conditions at the place you are making it.

Friendship Quilt

The most captivating custom is that of the Friendship Quilt. This quilt could be any pattern, with the added feature of a number of names embroidered on the squares themselves. Often each lady who had a part in the quilt embroidered her own name in the square she had contributed. As Mrs. Tom Kelly told us recently, “The girls had a custom of making Friendship Quilts. One person would piece a quilt block, and she’d give it to another girl, and keep on till she had enough blocks to make a quilt, and then all those girls would get together and quilt that quilt. And the one that started it around got the quilt. That was a very common thing in my girlhood days. The name of everyone that pieced a square was supposed to be put on the quilt, and they valued them. It was a keepsake really.”

Such quilts were made by the ladies of Rabun county, Georgia whenever a young person from that community got married, when a neighbor lost his house by fire, for a newborn child in the neighborhood, or just for a keepsake. When a boy became a man, he sometimes received one too; Edith Darnell explained: “We made ’em along when th’boy’s about your age. You know, everyone sent out—their family’d send out—a square, and everybody’d piece one for it. Everywhere th’square went, everybody pieced one to go with it. When they got th’ quilt done, all that pieced th’square went and helped quilt it. Then they’d wrap that’n [the boy they had done the quilt for] up in th’quilt when they got it done.”

https://publicism.info/labor/household/2.html