Sergei Eisenstein / Walter Benjamin

Please allow 10 working days to process before shipping

Garment Dyed - Wine Short Sleeve

100% Combed Ring Spun Cotton

Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Eisenstein was a Soviet film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is noted in particular for his silent films Strike, Battleship Potemkin and October, as well as the historical epics Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible. In 1915, Eisenstein enrolled in the Petrograd Institute of Civil Engineering to study architecture and engineering, following in his father’s footsteps. The 1917 Russian revolution disrupted that trajectory, presenting Eisenstein with both unimaginable freedom and unfathomable challenges.

While his father supported the old Tsarist regime, Sergei joined the Russian Army and spent three years working first on military engineering projects and later on propaganda for the young Soviet state. In 1920 he moved to Moscow and joined the first workers’ theatre, Proletkult, initially as a set designer and later becoming an artistic director. In 1921 he enrolled in directing courses led by Vsevolod Meyerhold, who would become his mentor and surrogate father figure. Thus Eisenstein’s directorial career was launched. He would later reflect in his memoirs that “the revolution gave me the most precious thing in life – it made an artist out of me. If it had not been for the revolution I would never have broken the tradition, handed down from father to son, of becoming an engineer… The revolution introduced me to art, and art, in its own turn, brought me to the revolution…”.

Yet, as this statement demonstrates, it was not only the political agenda of the October revolution that was at stake for Eisenstein; in grappling with one of the main historical events of the 20th century he was also grappling with a revolutionary transformation of the arts themselves, the freedom to experiment and renew, the idea that art could contribute powerfully to the social transformation of the world and consciousness.

Soviet Montage

Soviet Cinema came to being from its painful post war experience. With a strict control by the Government on film making and import of films, Eisenstein and Lev Kuleshov formed a group with other major directors like Dziga Vertov called “Association of Revolutionary Cinema” (ARC) which eventually broke up, but with the aftermath of the revolution, it brought forward a style called Montage that made the world pay attention to their cinema.

The war and the restriction brought a change in the Soviet Cinematic style. The primary principle of the montage style at this time was invented by Kuleshov in 1918 called the “Kuleshov Effect”, best shown in his short film in which a shot of the expressionless face of Tsarist matinee idol Ivan Mosjoukine was alternated with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl in a coffin, a woman on a divan). The film was shown to an audience who believed that the expression on Mosjoukine's face was different each time he appeared, depending on whether he was "looking at" the plate of soup, the girl in the coffin, or the woman on the divan, showing an expression of hunger, grief, or desire, respectively. The footage of Mosjoukine was actually the same shot each time.

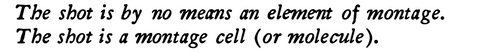

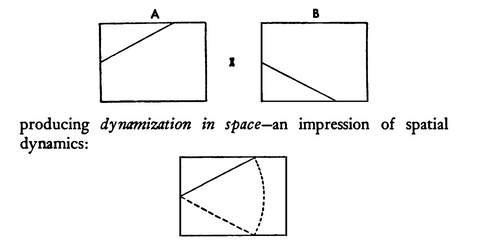

Eisenstein, taking this montage effect further, felt the collision of one shot or montage cell with another as creating conflict that produced a new idea. This new idea would become its own thesis and collide with another anti-thesis creating yet another synthesis idea. Again and again these dialectics build up in a film like a series of controlled explosions in an internal combustion engine, driving the film forward.

On the subject of editing Eisenstein lists five methods of montage or how these collisions between shots can be created, each one building up in complexity.

- The first and most basic is the Metric - cutting based purely on the length of shot. This elicits the most basic emotional response, that of tempo which can be raised or lowered for effect.

- Next is Rhythmic montage - which is much like metric montage in that it’s based on time and tempo, but rhythmic concerns itself with what’s in the frame - cutting in tempo and with action. In this shot from Potemkin, the rhythm of the marching soldiers legs drives the movement in the sequence beyond the basic cut..

- Next in complexity is the Tonal montage which isn’t concerned with time but with the tone of the shot - from lighting, shadows and shapes in the frame. Cutting between shots of different aesthetic tones creates these Marxist dialectics

- Above that is Overtonal - which is on a larger scale macro cell that combines metric, rhythmic and tonal montage - essentially how whole sequences play against each other.

- Then lastly was the type of montage that most interested Eisenstein - the Intellectual or ideological montage. Whereas the previous methods focused on inducing emotional response, the intellectual montage sought to express abstract ideas by creating relationships between opposing visual intellectual concepts.

A simple example in Battleship Potemkin, one of his most famous films, is the intercutting of the priest tapping on a cross with an officer tapping on the hilt of a sword - to express a message of corrupt association of the church and the state. Another example is the final sequence in the Odessa steps. Three quick shots of a rising stone lion - representing the rise of the proletariat.

Eisenstein was the most outspoken and ardent advocate of montage as a revolutionary form. His work has been divided into two periods. The first is characterized by "mass dramas" in which his focus is on formalizing Marxist political struggle of the proletariat. His films, Strike and The Battleship Potemkin, among the most noted of the period, centered on the capacity for the masses to revolt.

The second period is characterized by a shift to individualized narratives that sprang from a synchronic understanding of montage inspired by his foray into dialectical materialism as a guiding principle. The shift between the two periods is indicative of the evolution of Marxist thinking writ large, culminating in an understanding of the material underpinning of all social and political phenomena. Though largely uncredited by contemporary filmmakers, Eisenstein's theories are constantly demonstrated in films across genres, nations, languages and politics.

“Montage is a beautiful word.” writes Eisenstein, “One does not create a work, one constructs it with finished parts, like a machine…“ - Sergei Eisenstein

A Dialectic Approach to Film Form

In his essay A Dialectic Approach to Film Form, Eisenstein puts forward a “dynamic philosophy of things: Being - as a constant evolution from the interaction of two contradictory opposites. Synthesis - arising from the opposition between these and antithesis”. Just as Goethe says: “In nature we never see anything isolated, but everything in connection with something else which is before it, beside it, under it, and over it.”

Eisenstein adopts the theory of dialectics into art. Where the dynamic force that animates art is given as a series of conflict: conflict of social mission, nature and methodology.

“A dynamic comprehension of things is also basic to the same degree, for a correct

understanding of art and of all art-forms, In the realm of art this dialectic principle of

dynamics is embodied in CONFLICT as the fundamental principle for the existence of every art-work and every art-form.

For art is always conflict:

- According to its social mission,

- According to its nature,

- According to its methodology.

According to its social mission because: It is art's task to make manifest the

contradictions of Being. To form equitable views by stirring up contradictions within the spectator's mind, and to forge accurate intellectual concepts from the dynamic clash of opposing passions.

According to its nature because: Its nature is a conflict between natural existence and creative tendency. Between organic inertia and purposeful initiative. Hypertrophy of the purposive initiative – the principles of rational logic – ossifies, art into mathematical technicalism. Because the limit of organic form (the passive principle of being) is Nature. The limit of rational form (the active principle of production) is Industry. At the intersection of Nature and Industry stands Art.

Walter Benjamin

Walter Benjamin was a German Marxist literary critic. Born into a prosperous Jewish family, Benjamin studied philosophy in Berlin, Freiburg, Munich, and Bern. He settled in Berlin in 1920 and worked thereafter as a literary critic and translator. His half-hearted pursuit of an academic career was cut short when the University of Frankfurt rejected his brilliant but unconventional doctoral thesis, The Origin of German Tragic Drama (1928). Benjamin eventually settled in Paris after leaving Germany in 1933 after Hitler came to power. He continued to write essays and reviews for literary journals, but when Paris fell to the Nazis in 1940 he fled south with the hope of escaping to the US via Spain. Informed by the chief of police at the Franco-Spanish border that he would be turned over to the Gestapo, Benjamin committed suicide.

The posthumous publication of Benjamin’s prolific output won him a growing reputation in the later 20th century. The essays containing his philosophical reflections on literature are written in a dense and concentrated style that contains a strong poetic strain. He mixes social criticism and linguistic analysis with historical nostalgia while communicating an underlying sense of pathos and pessimism. The metaphysical quality of his early critical thought gave way to a Marxist inclination in the 1930s. Benjamin’s pronounced intellectual independence and originality are evident in the extended essay Goethe’s Elective Affinities and the essays collected in Illuminations.

The approach to art of the USSR under Stalin was typified, first, by the persecution of all those who expressed any independent thought, and, second, by the adoption of Socialist Realism - the view that art is dedicated to the "realistic" representation of - simplistic, optimistic - "proletarian values" and proletarian life. Subsequent Marxist thinking about art has been largely influenced by Walter Benjamin and Georg Lukács however. Both were exponents of Marxist humanism who saw the important contribution of Marxist theory to aesthetics in the analysis of the condition of labour and in the critique of the alienated and "reified" consciousness of man under capitalism. Benjamin’s collection of essays The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936) attempts to describe the changed experience of art in the modern world and sees the rise of Fascism and mass society as the culmination of a process of debasement, whereby art ceases to be a means of instruction and becomes instead a mere gratification, a matter of taste alone. "Communism responds by politicising art" - that is, by making art into the instrument by which the false consciousness of the mass man is to be overthrown.

The Work of Art In the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Perhaps Walter Benjamin's best known essay, "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," identifies the perceptual shift that takes place when technological advancements emphasize speed and reproducibility. The aura is found in a work of art that contains presence. The aura is precisely what cannot be reproduced in a work of art: its original presence in time and space. He suggests a work of art's aura is in a state of decay because it is becoming more and more difficult to apprehend the time and space in which a piece of art is created.

During the Nazi régime, Benjamin wrote the essay to produce a theory of art that is "useful for the formulation of revolutionary demands in the politics of art" in a mass-culture society; that, in the age of mechanical reproduction, and the absence of traditional and ritualistic value, the production of art would be inherently based upon the praxis of politics. This essay also introduces the concept of the optical unconscious, a concept that identifies the subject's ability to identify desire in visual objects. This also leads to the ability to perceive information by habit instead of rapt attention.

The Preface presents Marxist analyses of the construction of a capitalist society and of the place of art in such a society, in the public sphere and in the private sphere; and explains the socio-economic conditions of society to extrapolate future developments of capitalism, which result in the economic exploitation of the proletariat, and so produce the social conditions that would abolish capitalism. Benjamin establishes that artistic reproduction is not a modern human activity, by reviewing the historical and technological developments of the mechanical means for reproducing a work of art, such as an artist manually copying the work of a master artist; the industrial arts of the foundry and the stamp mill in Ancient Greece; and the modern arts of woodcut relief-printing and engraving, etching, lithography, and photography, which are the industrial techniques that permit greater accuracy through mass production.

In the discussion of the aura of authenticity and physical uniqueness, Benjamin said that "even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: Its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be"; and that the "sphere of authenticity is outside the technical sphere" of the reproduction of artworks. Therefore, the original work of art is an objet d'art independent of the copy; yet, by changing the cultural context of where the art happens to be, the mechanical copy diminishes the aesthetic value of the original work of art. In that way, the aura — the unique aesthetic authority of a work of art — is absent from the mechanically produced copy

Shock Effect, Distraction, Tactility

In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Benjamin writes that film has within its technical structure the property of producing shock effects in the viewer. These shock effects cause consciousness to protect itself from overstimulation by screening off content which then gets recorded as memory traces. This shocking, so to speak, technical structure of film is then coupled with the fact that the same films are viewed quasi-simultaneously by the masses as opposed to the careful attentive contemplation of an individual art aficionado. The mode of participation of these masses is one of distraction, not concentration. Moreover, Benjamin asserts that when the masses participate with film, or any other art, in a state of distraction they unknowingly absorb the content of the work of art.

Given that film has within its formal structure shock effects which beget memory traces not manifest to consciousness, aided by a mode of participation that is one of distraction, the masses then absorb much of the content of films without being contemplatively aware of either the absorption or much of the content itself. Any art that is absorbed in a state of distraction does so primarily by means of tactile as opposed to optical means. The tactile is primary and largely informs the optical reception which takes the form of distracted casual noticing and not attentive contemplation. Benjamin then contends that this tactile absorption that one finds in film is best understood in terms of an analogy with architecture and that its mode of reception by the distracted masses serves as a paradigmatic example and helpful analogy for understanding the distracted masses and how they participate with film.

Politicization of Aesthetics

The aestheticization of politics was an idea first coined by Benjamin as being a key ingredient to fascist regimes. Benjamin said that "fascism tends towards an aestheticization of politics", in the sense of a spectacle in which it allows the masses to express themselves without seeing their rights recognized, and without affecting the relations of ownership which the proletarian masses aim to eliminate. The counter response to the reactionary aestheticization of politics is the politicization of art. In this theory, life and the affairs of living are conceived of as innately artistic, and related to as such politically. Politics are in turn viewed as artistic, and structured like an art form which reciprocates the artistic conception of life being seen as art.

"Politicization of art" has been used as a term for an ideologically opposing synthesis, sometimes associated with the Soviet Union, wherein art is ultimately subordinate to political life and thus a result of it, separate from it, but which is attempted to be incorporated for political use as theory relating to the consequential political nature of art.

In Benjamin's (original) formulation, the politicization of aesthetics was considered the opposite of the aestheticization of politics, the former possibly being indicated as an instrument of "mythologizing" totalitarian Fascist regimes. In that light, the politicization of aesthetics was associated with a revolutionary praxis, a redeeming force, solace, undertoned by the fact that it represented a means to cope in such as the case of a restrictive, censorship enforcing society. It painted within a frame, so that something was put in place as a psychological incentive for survival, depending on a story dissolute outside of that frame - the story of a somehow socially asocial or asocially social individual able to transcend mundane surroundings and scenery, having an "ascetic scale", a ladder, maybe, at hand.

Mickey

Eisenstein had a unique relationship with the animated work coming out of Walt Disney Studios. He found the imaginative way in which Disney physically manipulated characters for utilitarian purposes to be the key element in the appeal of those films. He also responded to the magic of how later Disney films took what he saw as a functionally “grey” world and contrasted it with cartoons that “blazed with color.”

Eisenstein said that “if it moves, then it’s alive.” In the animated Disney short Plane Crazy, the lines are blurred between the animate and inanimate; characters that move become stationary, and objects that were at first motionless become almost fluid in form. Giving movement to things which could not move previously both draws attention and appeals to humanity’s older animistic tastes. Eisenstein posited that when Disney used this plasmatic approach to his characters, he breathed life into everyday objects, offering a pleasing contrast to the unwaveringly rigid structure of the modern world.

Benjamin says “Mickey Mouse proves that a creature can still survive even when it has thrown off all resemblance to a human being. He disrupts the entire hierarchy of creatures that is supposed to culminate in mankind. These films disavow experience more radically than ever before. In such a world, it is not worthwhile to have experiences. Similarity to fairy tales. Not since fairy tales have the most important and most vital events been evoked unsymbolically and more unatmospherically. All Mickey Mouse films are founded on the motif of leaving home in order to learn what fear is. So the explanation for the huge popularity of these films is not mechanization, their form; nor is it a misunderstanding. It is simply the fact that the public recognizes its own life in them.”

Eisenstein & Benjamin

Both Eisenstein and Benjamin see revolutionary potential for the new art of cinema and its ability to break with tradition. For Benjamin, cinema has the potential to do nothing less than break down the power structures of society. For Eisenstein, cinema breaks down classical modes of representation, thus creating meaning beyond that made possible by language or even the moving image of the conventional film. Both see film as the place where nature and science meet, and therefore as the art form best suited for the masses of the post-industrial era.

Informed by Eisenstein and his attempt to integrate physiological, emotional, and intellectual forms of response, Benjamin renders montage as the only vessel to activate the viewer and to position him as a critical reader rather than a detached consumer of images. Although Benjamin never discusses particular Russian avant-garde films in further detail, his understanding of cinematic communication as a process of shock, disruption, and spectatorial stimulation clearly draws from Eisenstein's early notions of montage cinema. Like Eisenstein, Benjamin conceives of montage as a technique that defines the specificity of cinematic representation against the other art forms, a method of expression and address that at once interrupts a continuous flow of associations and incites the viewer to intellectual responses.