Shakers / Rockers

Please allow 10 working days to process before shipping

White Short Sleeve

100% Combed Ring Spun Cotton

Rock My Religion

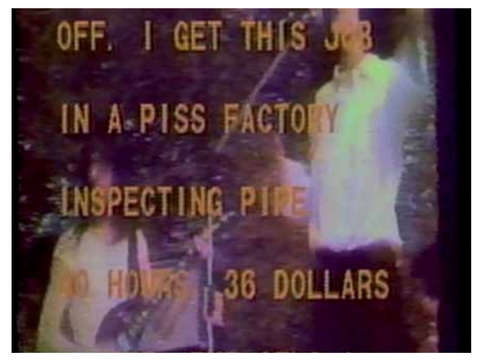

Rock My Religion is a documentary by Dan Graham consisting of an assemblage of stories, music, text, and film that examines and reconstructs the relationship between alternative religions and rock music in their development and practice. The video opens with punk musicians wildly shaking their bodies onstage to the sound of an electric guitar, alternating with woodcut illustrations of Shakers, members of the religious movement named for the fervent dancing and writhing they performed to purify themselves of evil.

The opening soundtrack layers and alternates between Graham's voice telling the story of Ann Lee, the Shaker who believed she was the second coming of Christ, and the music and voice of Patti Smith, an innovator of punk-rock music who has compared rock culture with religion. Rock My Religion continues by exploring historic American religious practices, including Native American, Puritan, and Shaker rituals, and the emergence of rock musicians like Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis, and The Doors.

Rock is interpreted as a religion with the potential for communal transcendental experience, but one that inverts traditional pieties with sexualized religious dance. Graham focuses on the social and sexual origins and implications of rock and roll, and his historical reconstruction provides a framework for the interpretation of the rituals of rock and punk culture as forms of religious practice.

Graham’s explanation of the design principles of the Shaker community was informed by a close reading of Dolores Hayden’s Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism 1790-1975. According to Hayden, the Shakers described themselves as a ‘living building’ that articulated ‘questions of order, sharing and visibility’.

Their book of ‘Millennial Laws’ systematized every aspect of their daily lives, structured according to a ‘spatial organisation’ of segregated domestic space maintained by a hierarchy of Elders and Eldresses. Graham visited Amerika Haus in Munich to ‘see books on the Shakers which the German middle-class lovers of Shaker decoration would buy’. These design fans made a ‘connection between Shaker furniture and Minimal art’.

On Sundays, the Shakers worshipped by dancing in circles that developed into pantomimes of temptation and fits. Graham wanted to ‘offset’ the contemporary perception of the Shakers by emphasizing that they were ‘very much more involved with a sexual kind of utopia, a kind of utopia based on having men and women live together but not have sex’.

Rock My Religion desublimates the middle-class fascination with Shaker decoration by connecting the images of Shaker interiors calculated to appeal with images of Minor Threat and Sonic Youth gigs designed to repel: it records illustrations of the Shakers’ bodies and animates them by the distorted live recording of ‘Shakin’ Hell’; it moves from the morning light of the Shaker residence to the barely legible darkness of the mosh pit.

The spatial order of a Shaker residence gives way to the cavernous depths of the Minor Threat gig. The distortion of the latter is interrupted by four beats of silence in which an unknown drummer silently yells as he pounds out a rhythm. The obscurity surrounding the drummer is dispelled by the light thrown onto tools hanging on hooks fixed to the slanted wooden planks of the Shaker walls.

The muted image of Ian MacKaye, pacing the floor, dressed in a black T-shirt, yelling into his microphone is crowded by the threats of ‘Shakin’ Hell’, which continues as the white text on vibrant orange describes how ‘a fit of shaking passed over the group’.

Kim Gordon appears for the first time at 10:32, shouting into her microphone. Her white arms are visible in the darkness, her elbows pointing downwards as she moves her shoulders in time to the pounding drum. For the first time, ‘Shakin’ Hell’ is reconnected with its own image. In doing so, it invokes the visual memory of the other images that appeared as it played: factory illustrations, drawings of Shakers, muted images of Black Flag. It recalls them in the altered form of auditory memories. Each visual memory conjures its auditory dimension: the rhythms of a Manchester factory, the pounding of shoes in a Shaker church in New Lebanon, the grinding guitars and yells of a Black Flag gig.

The music of ‘Shakin’ Hell’ plays also throughout the pan across the central figures of a drawing titled The Gift of Love, Evening Meeting, by A. Boyd Houghton, published in The London Graphic in 1870. The medium shot of The Whirling Gift, a line drawing by an unknown artist from David R. Lamson’s Two Years’ Experience Among the Shakers, is followed by the dramatic jump cut to a woman lying on the floor, a detail of the drawing. When Gordon reappears, her shoulders hunch and sink in time to the beat. She growls and snarls into the microphone. Her bass guitar bangs against the lower half of her silver dress. Graham’s camera shakes. Gordon’s performance is interrupted by white text: ‘singing begun after a violent jerking of head from side to side’.

As the text scrolls, whoops can be heard. These yells announce the presence of the religious revivalism that plays an important role in Rock My Religion. ‘Shakin’ Hell’ dramatises the Shakers’ demonology of desire as the first episode in Rock My Religion’s speculative account of ‘the making of Americans’, to borrow Gertrude Stein’s phrase. Graham concentrates on white Americans born in the flames of Christian fundamentalism; the Puritan sermon, the Salem witch trials and the Second Great Awakening are envisioned as moments in a political discourse that understands itself in the language of witchcraft and demons.

Anti-Parent Record

Black Flag’s debut album Damaged was released with a distribution deal with Unicorn, which was associated with MCA Records, resulting in an initial pressing of 25,000 copies. MCA Records president Al Bergamo listened to the album prior to release and claimed that it was "anti-parent", although he never cited a specific lyric that led him to that conclusion. As a result, MCA refused to distribute the already pressed and packaged album which bore an MCA Distributing Corp. logo on the lower right corner of the back cover. Black Flag members had to personally visit the pressing plant and apply a sticker over the MCA logo which read, "As a parent ... I found it an anti-parent record"—thus essentially throwing Bergamo's words back in his face.

Shakers

The Shaker utopian community is the quintessential commune to which all other utopian communities are compared. The Shakers, named after their ecstatic dancing as worship, are the longest-lived American utopian experiment. Shaker influence can be widely seen in fashion, furniture, textiles, and music. Moreover, they were radical for their time in many ways; 75 years before emancipation and 150 years before suffrage, Shakers were already practicing social, sexual, economic, and spiritual equality.

The Shakers developed their own form of communalism (religious communism) and developed written covenants in the 1790s. Those who signed the covenant had to confess their sins, consecrate their property and their labor to the society, and live as celibates. If they were married before joining the society, their marriages ended when they joined. A few less-committed Believers lived in "non-communal orders" as Shaker sympathizers who preferred to remain with their families. The Shakers never forbade marriage for such individuals, but considered it less perfect than the celibate state.

The Shakers practiced communal living, where all property was shared and were connected to many reform movements of the 19th century, including feminism, pacifism, and isolationism. Fugitive slaves, including Sojourner Truth, visited the Enfield Shaker community in Connecticut. Furthermore, the Shakers became notable for their craftsmanship, because, according to Shaker tradition, God dwelt in the details and quality of their work. Ann Lee's followers testified that she had many "spiritual gifts," including visions, prophecy, healing hands, and "the power of God" in her touch. The Shakers appreciated the revival tradition and brought those practices into Shaker worship.

Gift Drawings

According to Shaker tradition, heavenly spirits came to earth, bringing visions, often giving them to young Shaker women, who danced, whirled, spoke in tongues, and interpreted these visions through their drawings and dancing. The immense spirituality expressed through visions and spiritual inspiration, with periodic revivals of enthusiastic worship, revitalized their meetings.

Several pieces of art were created as part of the manifestation in New Lebanon, New York, and Hancock, Massachusetts. These were called "gift drawings" and depicted visions received by the Shakers during this time. Shaker founders and early leaders had often preached about heavenly treasures greatly to be desired. Never before, however, had Shakers dared to picture these heavenly treasures. Never before had Believers seen with their eyes the close formal resemblance between the things of eternity and the things of time. The subject matter and form of the instruments' images had been prohibited for many years as a threat to the purity of the sect. But a celestial content tempered and made useful this potentially radical art.

They were made with "painstaking precision" using watercolors or transparent inks. They generally included many small emblems, considered "wildly extravagant by Shaker standards," such as treasure chests, heavenly mansions, golden chariots, flowers and fruits, and included written messages of friendship or reverence, with calligraphic intricacies, resembling fine lacework. Generally, works would not be signed by the artist. The tree of life has become an icon to represent Shakers. Some of these "drawings" are now part of the American Folk Art Museum collection. Key artists from the Shaker community were Hannah Cohoon, Polly Collins and Joseph Wicker; others include Sarah Bates and Polly Anne Reed.

Hannah Cohoon

Hannah Cohoon joined the Shaker community in 1817 at the age 29. During a time of revival known as the Era of Manifestations, she produced several gift drawings and her works have become iconic of Shaker religious expression. Uncommonly for Shaker gift drawings, she signed her drawings, so that the works have been attributed to her. Cohoon had a unique style that was more abstract, simple and personal. She adopted a unique approach for her drawings where she used thick paint in primary or secondary colors that created an impasto texture, using bold, expressive brushstrokes. Her compositions were dedicated to a single object or scene with geometric patterns. Rather than messages intended for others, she wrote directly of visionary experiences, and she signed her works.

Cohoon is primarily known for her spirit drawings with trees: The Tree of Life or Blazing Tree, 1845, The Tree of Life, 1854 and A Bower of Mulberry Trees,1854. A Bower of Mulberry Trees was made as a result of Cohoon's vision of a feast of cakes by Shaker elders under mulberry trees. The depiction of the long table in the drawing represents holy feasts held in biennial meetings and the presence of the doves overhead represents the bounties that the believer would experience in heaven. Germaine Greer, author of The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work, likened Cohoon's drawing to primitive art by Catholic artists of "an earthly paradise with trees in flower and fruit. A "leading figure in the era of spirit manifestations".

Cohoon described how the vision came to her to create the Tree of Life drawing:

"I received a draft of a beautiful Tree penciled on a large sheet of plain white paper bearing ripe fruit. I saw it plainly, it looked very singular and curious to me. I have since learned that this Tree grows in the Spirit Land. Afterwards the Spirit showed me plainly the branches, leaves and fruit, painted or drawn upon paper. The leaves were check'd or cross'd and the same colours you see here. I entreated Mother Ann to tell me the name of this tree which she did on Oct. 1st 4th hour P.M. by moving the hand of a medium to write twice over Your Tree is the Tree of Life."

Gift Songs

"The designers of these symbolic documents felt their work was controlled by supernatural agencies, gifts bestowed on some individual in the order, usually not the one who made the drawing." The same is true of the "gift songs" and other verbal works, and the invention of forms in both the songs and drawings is extraordinary, as is their resemblance to the practice of later poets and artists.

The Shakers composed thousands of songs, and also created many dances; both were an important part of the Shaker worship services. In Shaker society, a spiritual "gift" could also be a musical revelation, and they considered it important to record musical inspirations as they occurred. Scribes, many of whom had no formal musical training, used a form of music notation called the letteral system. This method used letters of the alphabet, often not positioned on a staff, along with a simple notation of conventional rhythmic values, and has a curious, and coincidental, similarity to some ancient Greek music notation.

Many of the lyrics to Shaker tunes consist of syllables and words from unknown tongues, the musical equivalent of glossolalia. It has been surmised that many of them were imitated from the sounds of Native American languages, as well as from the songs of African slaves, especially in the southernmost of the Shaker communities, but in fact the melodic material is derived from European scales and modes.

Most early Shaker music is monodic, that is to say, composed of a single melodic line with no harmonization. The tunes and scales recall the folk songs of the British Isles, but since the music was written down and carefully preserved, it is "art" music of a special kind rather than folklore. Many melodies are of extraordinary grace and beauty, and the Shaker song repertoire, though still relatively little known, is an important part of the American cultural heritage and of world religious music in general.

Shaker Furniture

The Shakers' dedication to hard work and perfection has resulted in a unique range of architecture, furniture and handicraft styles. They designed their furniture with care, believing that making something well was in itself, "an act of prayer". Before the late 18th century, they rarely fashioned items with elaborate details or extra decoration, but only made things for their intended uses. The ladder-back chair was a popular piece of furniture. Shaker craftsmen made most things out of pine or other inexpensive woods and hence their furniture was light in color and weight.

The earliest Shaker buildings in the northeast were timber or stone buildings built in a plain but elegant New England colonial style. Early 19th-century Shaker interiors are characterized by austerity and simplicity. For example, they had a "peg rail", a continuous wooden device like a pelmet with hooks running all along it near the lintel level. They used the pegs to hang up clothes, hats, and very light furniture pieces such as chairs when not in use. The simple architecture of their homes, meeting houses, and barns has had a lasting influence on American architecture and design. There is a collection of furniture and utensils at Hancock Shaker Village outside of Pittsfield, Massachusetts that is famous for its elegance and practicality.

At the end of the 19th century, however, Shakers adopted some aspects of Victorian decor, such as ornate carved furniture, patterned linoleum, and cabbage-rose wallpaper. Examples are on display in the Hancock Shaker Village Trustees' Office, a formerly spare, plain building "improved" with ornate additions such as fish-scale siding, bay windows, porches, and a tower.

Noguchi Chair

“New land, new home, new life; a testament to the American settler, a folk theater. I attempted through the elimination of all non-essentials to arrive at an essence of the stark pioneer spirit, that essence which flows out to permeate the stage.” Thus sculptor Isamu Noguchi described his set for the iconic 1944 ballet Appalachian Spring, choreographed by Martha Graham to a score by Aaron Copland.

The ballet follows a Husbandman and Wife in nineteenth-century Pennsylvania as they wed, move into a farmhouse, and receive the blessing of a Revivalist and his Followers. A photograph of the empty stage taken in its original setting at the Library of Congress’s Coolidge Theater evidenced the austerity of Noguchi’s design. A house, a bench, a stone, a chair; Noguchi delineates each with plain wood, rendered ghostly white by the photograph’s dramatic contrast. The effect is nearly skeletal, as if flaying away the flesh of settlement to reveal its bones.

For the Shakers, simplicity and solid craftsmanship were understood as physical manifestations of spirituality, much like the vibrations that shook their bodies during prayer and were themselves quoted in the Revivalist’s frenzied choreography. The clean lines and meticulously fitted joinings of a rocking chair manifested the purity and unity of God’s perfection, recalling the Shaker proverb “Every force evolves a form.” The Shaker rocking chair’s embodiment of spiritual force serves as a touchstone for discussion of history and form, showing how the invisible forces around us may be made manifest, and in turn transform us. As Noguchi wrote of the set, “It is empty but full at the same time. It is like Shaker furniture”.

Every Force Evolves a Form

One problem with "form follows function" is that it is tautological—it presupposes that every form in the natural world exists as it does because of functional requirements. We start with the end result (the form), look backward toward its origins, and assume that the results were inevitable. But there are any number of reasons why something might have a particular form (chance, malevolence, whim, purposeful design, play, folly, and numerous combinations thereof).

A better, less tautological mantra comes from Mother Ann Lee, founder of the Shaker movement in America: "Every force evolves a form." From this perspective, form doesn't simply, dutifully follow a set of functional requirements. Instead, dynamic forces gradually forge resultant forms. These forces aren't simply functional; they can also be communal or spiritual, as was the case with the Shakers.

For working designers, "every force evolves a form" is a more useful rule. The design process actually begins with something that doesn't yet exist but needs to exist, and it moves forward toward a formal result. Function alone doesn't drive the resultant form. The form evolves from the holistic forces of the project—audience needs, client desires, ethical obligations, aesthetic inclinations, material properties, cultural presuppositions, and yes, functional requirements. "Function" is rightly seen as a single, isolated, quantifiable aspect of the overall "force" driving the form.

True, the Shakers did esteem utility. They found it beautiful. According to one of their slogans, "That which in itself has the highest use, possesses the greatest beauty." But more forces were bearing on the form of Shaker furniture than mere utility. The teachers of the Bauhaus also esteemed utility, but the forms of their furniture are far from identical to the forms of Shaker furniture because a host of other historical, philosophical, and material forces in addition to mere utility were affecting and evolving both forms.

Portfolio Mag & CBS Logo

Around the same time William Golden began his quest to develop a new CBS logo, Alexey Brodovitch, famous as the art director of Harper’s Bazaar, took on a new project – the publication of a magazine dedicated totally to graphic design. The magazine, Portfolio, was published without advertising, supported only by the subscriptions of those with a love for graphic design. Although Portfolio lasted only three issues, it achieved a reputation as the most significant publication on design during the twentieth century.

The first issue of the magazine included an article titled, “The Gift to be Simple,” (incidentally, part of the first line of the Shaker song, Simple Gifts) that featured a drawing, untitled and undated, attributed by style and choice of symbols to Sister Sarah Bates of the Mount Lebanon Shaker Community (now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection). It is a detail of the “all-seeing eye” selected by Brodovitch from the upper center of the drawing that caught Golden’s attention.

Luckily for Golden, Brodovitch chose to reproduce the eye from a black and white negative and printed it as a high-contrast image, accentuating the difference between the iris and the pupil. Golden, seeing the potential in the image, handed off the concept for the eye logo to Kurt Weihs, who was able to refine the drawing for its intended use. Weihs was the one who appears most clearly to remember the connection between the CBS Eye and the Shaker drawing in Portfolio magazine. The missing link in the story is how Alexey Brodovitch came to do an article about Shaker gift drawings in the premiere issue of Portfolio.

Sister R. Mildred Barker, from the Shaker community at Sabbathday Lake, Maine in making a point about the real significance of the Shakers in the world, said she did not “want to be remembered as a chair.” Shaker genius, however, expressed itself in many forms – design, invention, social justice, theology, and even the simple chair. The story of the development of the CBS Eye is one example of how the Shakers unintentionally inspired creative impulses in the outside world. In this case, Shakers experienced a spiritual vision. The vision was recorded by a scribe who created a tangible symbol of the all-seeing eye of God held aloft by the wings of an angel. The creative director for CBS used that inspiration to create an image in which the television network makes a case that it is an “eye” that will always be “looking at the world.”